A HERETIC'S NOTEBOOK By Om Prakash Deepak - Everyman's 1974

The great man and small men

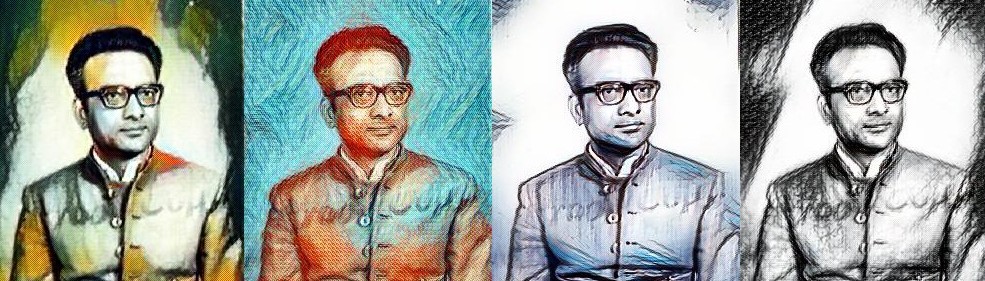

Prof. Satyen Bose was probably our greatest physicist at the time of his death a fortnight ago. The news of his death gave me a feeling almost of personal loss. The feeling was enhanced by the memory of an incident more than two decades back. After the first general elections, in which Socialists had fared badly, he saw a socialist leader in a Calcutta restaurant. Prof Bose went to him of his own accord and said they should take the defeat in their stride, victory for democratic socialism would not come easily. That apart, any country would be proud of a citizen like him.

For that reason alone I felt disgusted and angry beyond words when I heard newsreaders both of the radio and of the TV talking of the impending miners’ strike in UK and God knows what else. After a couple of minutes I was not listening. They probably announced his death at the fag-end of the bulletin in a single sentence. But more was yet to come. I was astounded by what I saw in the papers next morning. The president had sent his condolence message to the governor of West Bengal. Universities in West Bengal were closed for the day. Some Bengali medium schools in Delhi were also closed.

Did the President of India and the Chief Minister of Bengal think that Prof Bose belonged to Bengal alone? His death is an irreparable loss to the whole country, and the whole country should have mourned his loss, as I am sure, countless people did, who knew him or any that thing about him. It is through incidents like these, that the rulers probably consider insignificant that the unity of a nation, is irrevocably damaged.

I can understand the ruling class being peeved. A prominent journal published from Delhi even commented in its obituary, that Pro Bose was “obsessed” with his mother tongue. He wanted the knowledge of science to be spread through it. The comment was both petty and silly. Prof. Bose was among those who believed that the knowledge of science in India cou1d not really be spread medium of English. It could be done only through the mother-tongue of the student, be it Bengali, or Tamil or Hindi. His own mother tongue and that of his students was Bengali so he delivered his class lectures in that language. But Bengal is a part of India and Bengali is one of India’s major languages, both rich and sweet.

I can also understand the Bangladesh Prime Minister’s remark that Prof. Bose was a great son of Bengal. But it was not in very good taste. He should have said that Prof. Bose belonged to all Bengal as be belonged to all India. But what is one to say of India’s rulers whose conduct confined that great scientist to Bengal alone.

I was not surprised to learn that Prof Bose was not paid his salary as national professor for several months while he was lying ill. After all, he didn't belong to the corrupt set.

Gandhi and Modernists

The argument that Gandhian economics is backward-looking is not new. To the surprise and consternation of our ‘ultra (sic) moderns’, however, many outstanding Western scholars from Gunnar Myrdal to Schumacher, have come out with statements in the recent past that Gandhi understood India’s objective conditions better than anyone else, and his approach to the country's problems was the only really modern one. Now, once again we hear people saying that if India adopted the Gandhian way of small scale technology, we'd be cut off from the ‘progress’ of the world.

I do not know if this ghost of ‘progress’ can be laid so long as it sits on the shoulders of our rulers and policy makers. But, after all, there must be some test for progress. For one thing, are the achievements of the white races - good, bad, or Indifferent - synonymous with world progress? From Marx to Erikson there have been numerous well-meaning people in the west who thought or still think that the influence of British imperialism in India was on the whole good, for it brought India into direct contact with civilization and paved the way for India's modernization. Rails and roads, telegraph, telephones and wireless, electricity, mines and factories, ports and industrial towns, police and municipalities, schools, colleges and universities, a unified administration and a code of law, these and so many other things were brought or built in India by the British.

And, yet let us look at some elementary questions. Is the average citizen better fed today? Is he better clothed? Better housed? Is justice available to him as it should be? Is there greater equality in our society today than in the past. Except for the only real equality of an equal vote, the answer to all these questions, is an obvious no. And this when we have been strenuously pursuing the goal of progress on Western lines for more than a quarter century. All that we have succeeded in doing is to add to the list of things that the British had left, but at such enormous cost to the people and the country that we are at the brink of a catastrophe.

So, what is the progress from which it is feared we'd be left out if we tried to learn from Gandhiji? Affluence of the chosen few? Bureaucracies unrestrained power? Unproductive, wasteful, and ugly Multi-storied structures? What our so-called modernists do not seem to understand is that we pay for these things in the form of mass unemployment and increasing hunger among a majority of India’s population as also increasing illiteracy (however much it may surprise many readers, it is nevertheless true that the total number of illiterates in the country has been steadily rising and continues to do so), increasing injustice, and lawlessness.

Then, let us look at the West itself. The recent oil crisis has dramatically demonstrated how flimsy are the grounds on which Western progress stands and how easily and seriously are modern economies affected by the slightest adverse tilt in the system of international trade in which there is an inherent weightage at present in favour of technologically developed economies. It is true that the West will in all likelihood overcome the crisis after a period of trouble, but that again will be at the cost of less favoured peoples like us In India. But then, as I said earlier, the ghost cannot be laid so long as it sits on the shoulders of our rulers who go on celebrating with amazing loyalty one centenary after another of vestiges of the British Raj in India.

Probably it wouldn’t occur to the Prime Minister that she was being wholly, almost inane, when she said in the context of Gujarat, that violence doesn’t solve any problems. For one thing, all official spokesmen when they talk of violence, fail to take notice of the fact that the Indian state, on a conservative estimate, has killed anywhere between five to ten thousand of its citizens in the first twenty-five years of its existence.

In a free and comparatively equal society that alone would be enough to cause a violent revolution. Over and above that, countless citizens have died slowly, or suddenly, in pain as a direct result of official policies in the economic and social spheres.

I am not advocating or even justifying violence. Far from it. In fact, if I could, I would tell the sponsors and supporters of every popular agitation that stone throwing or petty arson is only a manifestation of weakness. But the Prime Minster’s policemen are all the time killing heaven knows how many men and women, and not only in Gujarat. Before she talks of futility of violence, she must put a stop to official murders. But, then, one may as well ask for the moon.

Good Neighbours

I would like to relate a personal experience, not very important in itself but possibly quite significant in terms of the relationship between the people of India and Bangladesh. In November last I applied for a passport but without getting endorsement for Bangladesh. I had to make a separate application for that. Then, as I am a journalist by profession my application was referred to the ministry of external affairs for clearance. The ministry, I was told had to refer it to some other organisations. Then they wanted from me a list of my old acquaintances in Bangladesh and other people that I was going to meet. It took them more than a month after that to send the clearance and my passport was endorsed on the 5th of Feb. 1974, nearly two and a half months after I had applied for endorsement.

I just do not understand all this. It was not incompetence or inefficiency. In fact, during my visits to the RPO’s office in New Delhi, I generally found that as government offices go, it functions quite well. Quite obviously some rules or government orders were involved. I don’t know what they are and who is responsible for them. But the fact remains that I could not have attended the Awami League conference held in Dacca in the third week of January had I wanted to do so, although I had applied for my passport two months earlier. Whether I would have gone or not, even if I had the passport and the endorsement in time, is not very relevant.

In fact the personal factor in the incident is not at all significant. It has wider implications. I don’t for a moment their right to independence – they have earned it through a great ordeal – but the people of Bangladesh are our own flesh and blood, and relations between the people in the two countries do not come under usual neighbourly relations: they are deeper and thicker than that. Any Government of India, with any amount of sense, should not only permit but encourage the greatest possible co-mingling among the people of India and Bangladesh. Was my experience the consequence of policies lacking in even that much of sense?

***

Back to the Home-Page - Index of Writings of Om Prakash Deepak